The Cause of Malocclusion

(the Mastantlos Hypothesis)

Three causes are suggested:

- Living in hoses with many allergens which cause allergies and open mouth breathing

- Soft foods which causes facial lengthening

- Feeding infants with spoon, cup or bottle before 28 months

The Mastantlos Hypothesis

Abstract

Objectives

We do not know how modern lifestyles may have influenced craniofacial growth, but evidence suggests that suction by the tongue when swallowing in young children is associated with narrow maxillary dental arches and retruded jaws.

Material

This study considers previous theories about tongue ties, the influence of oral posture, and the mechanics of breastfeeding and provides a hypothesis which may explain how they might relate to craniofacial development.

Conclusions

Breastfeeding is primarily thought to involve suction; however, the biomechanics of milk extraction also involves compression. The Mastantlos Hypothesis suggests that breastfeeding should involve a firm tongue to palate thrust, which encourages the maxilla to grow forward and widen. At the same time, it is suggested that firm thrusting will release many tongue ties. Bottle and spoon feeding are considered to disrupt tongue to palate posture and restrict forward facial growth.

Keywords: Breastfeeding, Tongue Ties, Tongue Posture, Facial Appearance.

Introduction

The dictionary definition of swallowing is “To cause food, drink, pills etc to move from your mouth into your stomach”. While this may be an oversimplification, most mammals swallow in a similar manner starting with the tongue pushing up on to the palate before the centre drops to initiate a peristaltic wave which carries the bolus down the oesophagus. Interestingly, many civilized humans do not swallow like that. They suck on their teeth collapsing the dentition and frequently creating narrow palates; why is this?

History

It has been suggested that malocclusion is largely due to adverse oral posture, but this is difficult to confirm as long-term posture is almost impossible to measure. Edward Angle, considered by many to be the ‘father’ of orthodontics, thought oral posture had a major influence on dento-facial development. However, following the extraction era started by Charles Tweed, a student of his, orthodontic treatment became more of a mechanical art. Teeth are now moved individually but subsequently require permanent retention, and most orthodontists accept that treatment has a retractive element which may have implications for the airway and the Temporo-mandibular joints.

Oral posture was addressed by the ‘Tropic Premise’ in 1981. It suggested that “the tongue should rest on the palate with the lips sealed and the teeth in or near contact”. This was thought to create an ideal face and dentition. It was broadly rejected at the time but 40 years later is popular with the public as ‘mewing’. It has to be accepted that oral posture has some influence on dento-facial development.

The Tropic Premise may describe how poor oral posture can cause human malocclusion, but it does not explain the reason why oral posture goes wrong. Mastantlos is an additional hypothesis intended to provide a logical explanation for this. Because oral posture cannot be measured, it remains without proof, but like the apple which fell on Newton’s head, many of the leaps in science have come from observational hypotheses.

All mammals suckle their young for various periods. Currently, the average period of human suckling appears to be about six months, although there are areas and groups where breastfeeding is longer or shorter. For several centuries now, bottle feeding has progressively supplanted breastfeeding, and strong views are expressed about the rival merits of each. It is not my intention to make recommendations but to consider the mechanics of breastfeeding and its possible long-term consequences on tongue posture and facial development, hoping this will assist both the specialty and the public to come to their own conclusions.

Long-term oral posture is very difficult to measure accurately, which is why the specialty has few recommendations to make on this subject. When evidence is unavailable, a rational assessment may be all we have.

The philosopher Karl Popper taught, ‘it is not possible to prove anything,’ and that it is more fruitful to examine the various hypotheses and adopt the one that fits the evidence best. I am suggesting that the ‘Mastantlos’ hypothesis provides an explanation for the forward growth of the dento-facial complex; in converse, it may also provide the reason for the current large number of narrow retruded maxillae.

Aetiology

The tongue develops as a small bulge in the floor of the mouth, before growing into a powerful muscular organ. Primarily it acts as a three-way valve, to occlude the mouth, the nose or the trachea but it also performs many other duties, placing food between the teeth, scouring for loose particles and of course speech. Perhaps most importantly, it acts in conjunction with the mandible to express the milk from the breast.

How might tongue size or activity affect the width and position of the maxilla? Few skulls have survived from our Palaeolithic past but their first molars appeared to be nearly 50 millimetres apart and around 12 millimetres further forward than current norms. In my estimation the width in modern man should not be less than 44 millimetres, or 42 millimetres for women.

Does firm tongue to palate posture assist with the forward placement and width of the maxilla? I am told that in past times Brazilian mothers used to suspend their babies in the air with their thumb against their palate to ensure good forward growth. Currently the average inter-molar width varies from country to country and in the United Kingdom is around 33½ millimetres2, which leaves insufficient room to accommodate a full dentition of 32 teeth.

Treatment Options

Narrow jaws are a major concern to dentists and orthodontists alike and the advantage of expansion has been realised since the arches were first widened by Pierre Fauchard in the eighteenth century. UK orthodontic teaching in the 1920s, suggested that if a 5 year old child did not have spacing between their deciduous incisors, they should be expanded. However the persistent relapse of this expansion, led to its unpopularity, even though it was rarely total. The research of Skieller, who used metal implants to measure the precise widening of the dental skeleton, showed that after expansion, most of the relapse was of the teeth which had tilted and that widening of the midline suture was largely permanent.

My father was also an orthodontist and kept good records. After his death I researched his expansion cases and found that most of them had relapsed by between one to two thirds of the expansion, but surprisingly some had hardly relapsed at all. What amazed me was that a few had continued to widen after expansion. This naturally set me thinking and is why I now believe that the position of the tongue has great influence on the width and position of the maxilla.

Many clinicians view the teeth and bone as rigid because of their ability to crush tough food. However in the long-term they are influenced by very light forces. Not surprisingly most research has concentrated on the ‘ideal’ or ‘fastest’ way of moving teeth and there has been little research on the minimum force required to move a tooth. Sam Weinstein’s classical research concluded that teeth would move with a force of under 2 gm. He thought that contact from the cheek was able to move teeth, suggesting a ‘stiffness’ of the cheek of 0.8 gm and a mean ‘resting force’ of 4.89 gm. He also thought that there might be a genetic factor in the stiffness.

More recent research suggests that the lowest force that will produce ‘optimal’ bodily tooth movement is between 50 and 100gm. However the optimal force for tooth movement need not equate with the minimal force. Also bodily movement is very different from tilting, so in reality we have little idea of the minimum force required to move a tooth.

My own rather primitive research, using blobs of composite resin on the lingual or buccal surfaces of unopposed teeth, led me to believe that one or two grams from the tongue or even a feather could move a tooth if applied for long enough. These thoughts enabled me to put forward the Tropic Premise where I suggested that if the tongue rests against the palate with the lips sealed, then the teeth will erupt between them to form an ideal arch and alveolar bone will form to support them.

I was then faced with many questions. Does life-style play a part in tongue posture? Might this be responsible for the increase in narrow jaws over the last 20,000 years? Could this be this be due to changes in habitat? Might changes in our current food texture or content play a part? Is facial and dental form related to tongue function or oral posture? Some authorities suggest that Tongue Ties provide a major restriction to tongue activity, while others say that ties resolve with time; are there common factors in these relationships?

Tongue Ties

The issue of tongue ties arose in the 1930s and again became prominent in the 1970s. Currently, many clinicians are again talking about their significance for both tongue action and malocclusion. However, there is still little convincing evidence either way.

There is no doubt that at times, ties restrict breastfeeding, but we have little information to tell us if these are inherited or the result of reduced or bizarre tongue activity. Discriminative research on breastfeeding is difficult because of the many variables. The issue is further confused by the wide distribution and descriptions of these ties. Even the evidence itself is conflicting and, in many cases, does not establish whether the ties restrict tongue movement, or if aberrant tongue movements permit the ties to be maintained, or finally, if ties need to be cut or can be stretched.

The developed tongue is attached by ligaments to the various bones around it, mainly to the hyoid below it but also to the mandible beside it and the skull above it. Muscles can only lengthen or shorten in straight lines, so to move the tongue in various directions, different muscles have to lengthen or contract.

Changes in shape of the body of the tongue are achieved by the intrinsic muscles. These are placed in different planes and are attached partially to each other and partially to the fascial sheaths which run between them. This gives them enough anchorage to extend the tongue, in some cases to the tip of the nose or chin, but on other occasions, the fascial attachments appear to limit the range of overall movement to varying extents.

As a baby grows from around 2½ to 55 Kilos, the cells divide and multiply millions of times, but many clinicians are unaware of the billions of cells that are removed and replaced during this process. Indeed, it has been suggested that we replace our entire body except our brain cells every ten years or so.

The removal of these living cells is called "Apoptosis" or “programmed cell death”. Dentists are familiar with this process during eruption, when the roots of the deciduous teeth dissolve as their permanent replacements erupt.

Many parts of the body are divided by fascial layers; for instance, the face forms from the fusion of three processes, and on each occasion, the fascial sheaths around them die so they can fuse. If this process fails, we may develop a cleft lip or palate. Fascial sheaths play a crucial role in guiding the growth and development of the whole body.

Could restrictive tongue ties be no more than residual fascial sheaths which, for some reason, have never apoptosised? From time to time, they restrict the normal activity of the tongue in both the young and old and need to be sectioned, but what is not so clear is why cell growth and apoptosis often fails. I doubt if even severe tongue ties prevent the tongue contacting the palate when the mouth is closed. These problems don’t seem to occur with other mammals, nor judging from their skeletons, in primitive humans either. Something must be wrong currently that was satisfactory until recently.

Changing Life-Styles

One of the most obvious changes over the last three centuries has been the reduction of breastfeeding and this has been paralleled by an increase of malocclusion. Could there be a biological or mechanical link here? As more women enter the workforce, their greater ambitions coupled with an increase in the age of childbirth, might well have an effect on the pattern and especially the period of breastfeeding.

Evidence from more primitive societies suggests that women used to breastfeed for three or perhaps more years. Obviously, the period depends on many factors but even one month of breastfeeding is said to bring benefits. Currently, the recommended period remains at around six months.

Tongue Function

We need more research, but it seems possible that a firm push of both the tongue and jaw helps to break down the fascial sheaths around the tongue. Recent research suggests that “Breast-feeding is the outcome of a dynamic synchronization between oscillation of the infant’s mandible, rhythmic motility of the tongue, and the Breast Milk Ejection Reflex (MER) that drives maternal milk toward the nipple outlet”.

I am sure that this is an accurate description of the rhythmic movement of the mandible and tongue against the breast, but I am not so certain about the “milk ejection reflex” because the only muscles in the breast help to erect the nipple. There is a lattice of myoepithelial cells that surround the alveoli, but it was established many years ago that the mammary pressure in pigs was no more than around 0.045 Bar (1.26 PSI). I am not sure that this is enough pressure to eject the milk down collapsible ducts in the quantities required without some assistance.

I believe that additional pressure is provided by the action of the tongue supported by the mandible, which pushes on the breast to assist in extracting the milk which is then swallowed by a peristaltic wave starting at the back of the tongue.

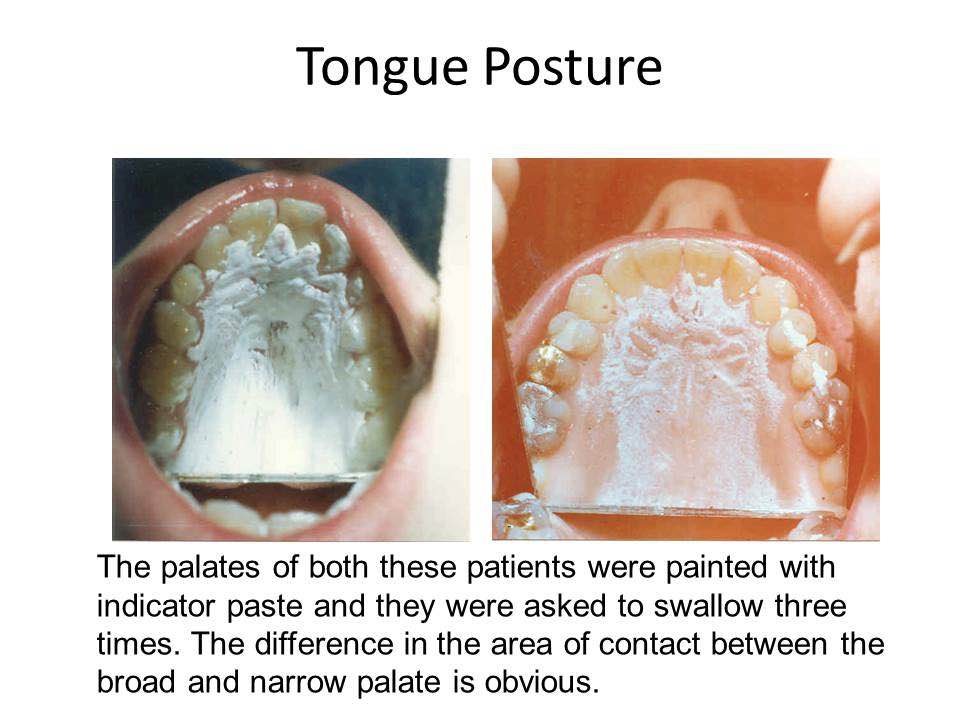

Sucking is not a very effective way of moving fluids as it relies on atmospheric pressure and soft ducts are at risk of collapse, unless they are supported, like the bronchi. Pumping is far more effective and clearly can be related to the rhythmic movements of the mandible and the tongue observed by Elad et al. Additional support for this concept comes from my own research on the palatal rugae. Figure 1 shows that a narrow palate will have raised rugae while a broad palate will have flattened rugae.

Figure 1

Swallowing Patterns

An important factor in dental health is the type of swallow pattern. According to Barrett and Hanson (16), infants suck with their tongue against the gum pads and later change to sucking with their tongue against their palate. They labeled these patterns as "juvenile" and "adult" respectively. However, the timing of the transition is controversial. Some suggest six months (17), while others suggest six years (16). In my opinion, the transition should occur around two and a half years, following the eruption of the deciduous molars.

Interestingly, the majority of individuals today never complete this change-over and continue to swallow by sucking on their teeth to some extent, which can lead to narrow, retruded jaws.

The recent reduction in breast feeding has led to an increase in bottle and spoon feeding. Bottle feeding requires suction rather than compression, which is a very different process. Many years ago, an inventive clinician created the Nulke (NUK) teat for bottle feeding, which encouraged babies to suck harder. I think it is more important for babies to learn an expressing action. When they are a few months old, many babies are introduced to supplemental spoon feeding, which occurs long before they have developed an adult swallowing pattern, and they naturally try to suck the spoon.

Mothers often gather food from around their child's mouth and reinsert it. This action unknowingly teaches their baby to suck their food, which can lead to the widespread human pattern of sucking on their teeth when swallowing, rather than pushing on their palate. This, in my opinion, is likely to collapse the dental arch and could be a factor in creating narrow maxillae and associated malocclusion.

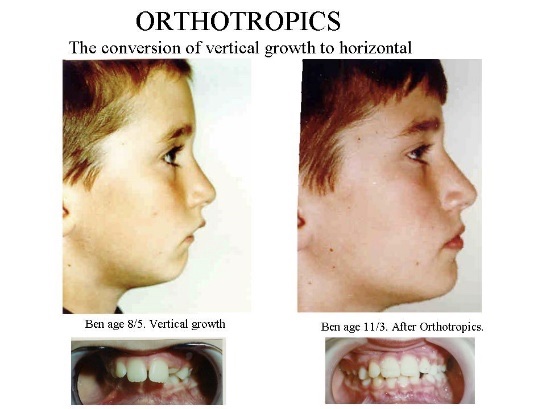

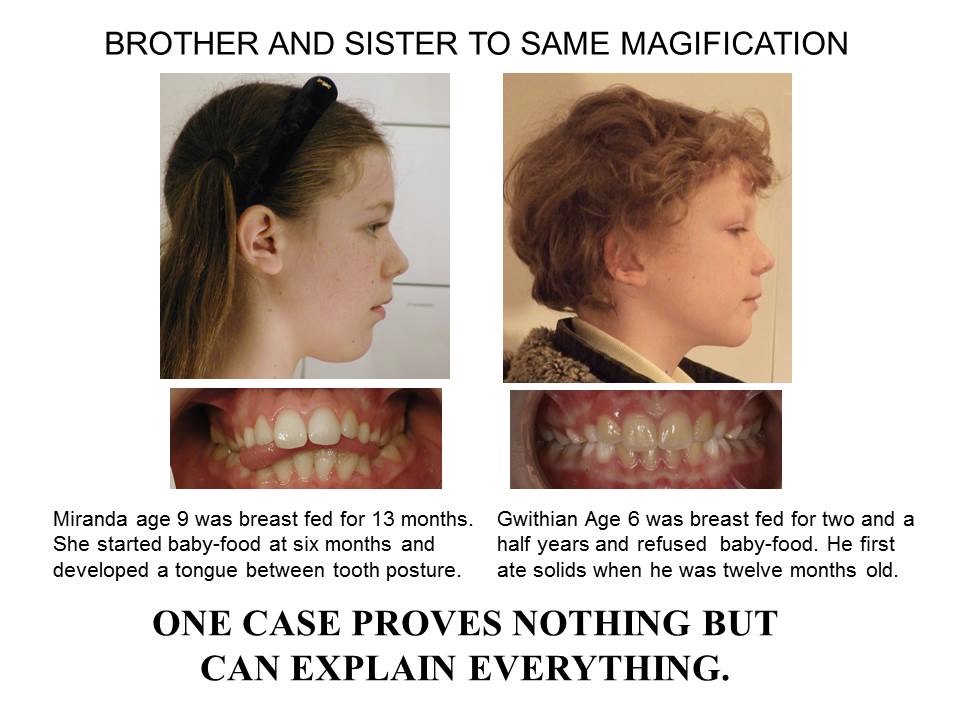

Clinical Examples

In 2004, I gave a consultation to a young girl with a severe malocclusion and noticed that her brother had an almost perfect occlusion (see Figure 2). Her mother gave me this explanation:

Figure 2

“When I had my first child Amanda, I did what many new mothers do, which was largely to follow the then prevailing advice on feeding. I did breast feed until she was thirteen months, but also dutifully began introducing pureed food from about five months. My first child was extremely compliant and seemed to enjoy her baby rice and later the home-prepared pureed fruit and vegetables”.

“Meanwhile, my second child, a son had a completely different experience in learning to eat and drink. I breast-fed him for two and a half years and for twelve months exclusively. This was his choice, rather than mine. I did try to introduce baby-rice at about six months, but he was resolute in his refusal to accept it. Periodically I would try to offer him pureed fruit, each time without success. At around twelve months he took a chip from someone else’s plate and ate that. This was his first solid food. He continued to refuse pureed food and has only ever eaten food that he could bite and chew. Dentists marvel at his jaw line”

Another mother reported:

“I didn’t get the diagnosed Tongue Tie treated. I didn’t want to put my baby through the weeks of wound stretching afterwards. This same child is now 4 and still breastfeeding. His craniofacial development is perfect.”

It appears that in this case the Tongue Ties apoptosised without difficulty, was this due to the continued breastfeeding? Could this be due to the continued breastfeeding? Interestingly, many mothers now choose to avoid pureed food altogether and instead introduce their baby to solid foods using an approach known as baby-led weaning 17

Discussion

Swallowing requires some suction to form a bolus, but then with the adult type swallow, the tongue pushes against the rugae and the margins of the palate before it drops in the centre to initiate a peristaltic wave. This works well if the tongue is pushing firmly on the palate but if the patient has maintained a juvenile swallow and is sucking on the teeth, air will be drawn in between the interstitial dental spaces, leaving them unable to achieve negative pressure.

To overcome this, those who suck on their teeth, have to seal these gaps with the Buccinator and Orbicularis Oris muscles. This means they have to close their mouth to suck and swallow. This contraction of these muscles can be seen and used to diagnose that they are swallowing incorrectly. Those who swallow with their tongue pushing against their palate can easily swallow with their lips apart, but faulty swallowers have difficulty doing so.

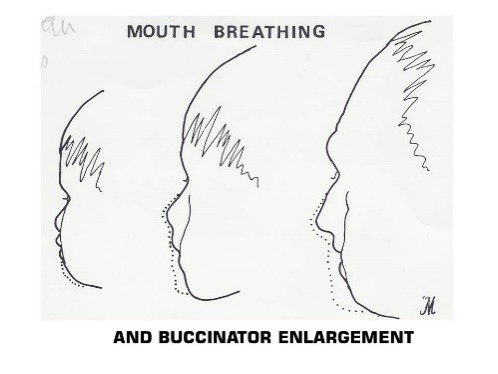

This retained juvenile pattern of swallowing can be recognised by the enlargement of the Buccinator Muscle and thickening of the lips because the cheeks become swollen or ‘bloated’ (Figure 3). Changing from a sucking swallow to a pushing swallow can alter facial form.

Figure 3

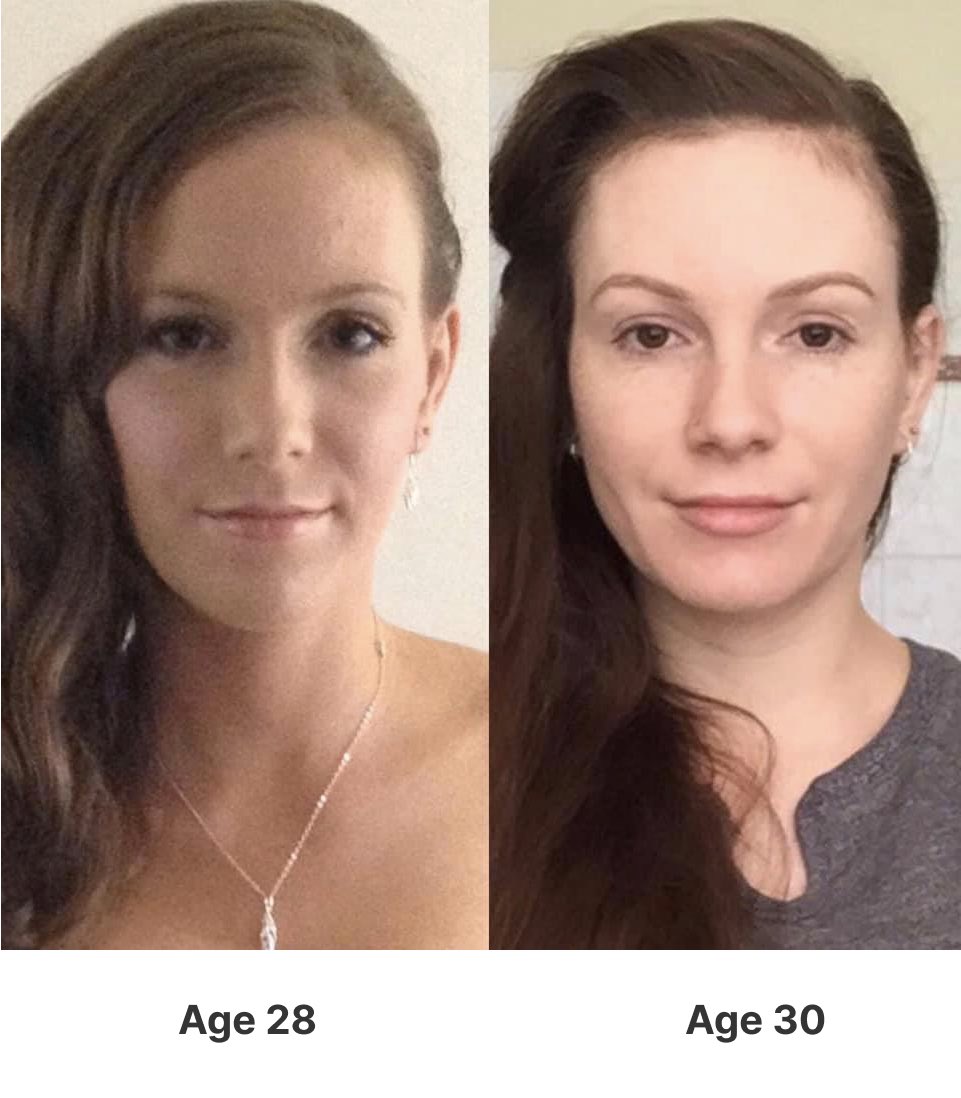

Rounded cheeks are natural in babies but they should later become thinner as the adult pattern of swallowing, is adopted and develop attractive hollows or ‘dimples’ in the cheek. Conscious training can convert bloated cheeks to hollow ones (Figure 3). The majority who fail to convert will develop bloated cheeks and become progressively less attractive as they age (Figure 4). Failing to achieve this can be the cause of ‘jowling’ in old age.

Figure 4

Conclusion

Maintaining tongue to palate posture is clearly important, and I believe maintaining a firm push on the palate when swallowing helps to take the maxilla forward and up. At the same time, I believe this push releases or stretches many restrictive tongue ties.

It seems that sucking on the teeth when swallowing increases long-term swelling or bloating of the cheeks. To help children avoid this, patients should be trained to keep their jaws closed when swallowing. This also appears to encourage forward growth of both jaws (Figure 5). Many teenagers and young adults now call this posture ‘mewing’ and claim to have improved their appearance, purely by changing their oral posture (Figure 6).