Indicator Line

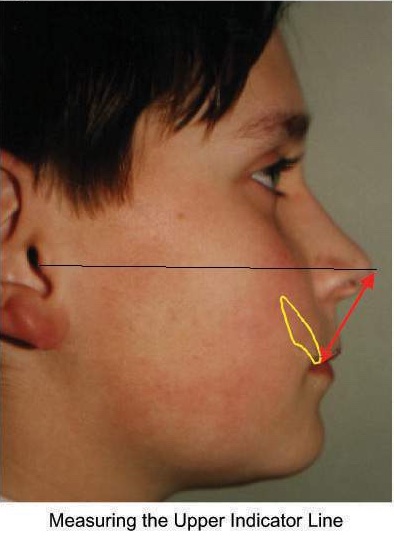

Figure 1

This is the distance from the tip of the nose to the incisal edge of the lowest upper central incisor (Figure 1). The tip of the nose is defined as the furthest point from the Tragus of the ear. The length of the Indicator Line is then related to average values for Caucasians (Figure 2)

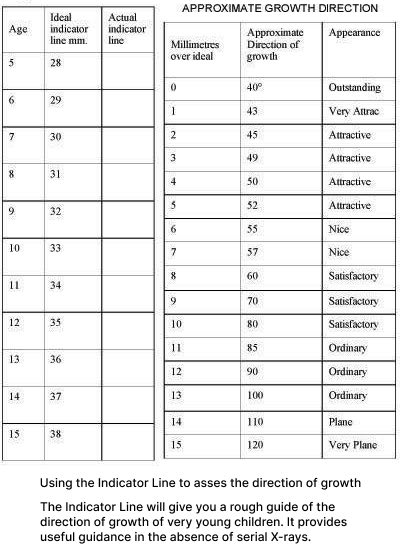

Figure 2

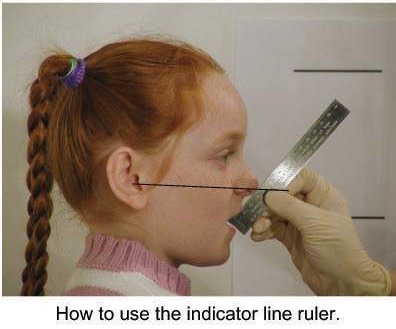

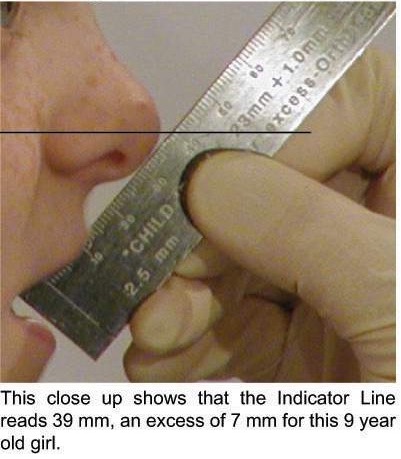

Scandinavians tend to be about 1mm greater and Orientals about 1 or 2 mm less, but as the values are only approximate this is hardly significant. We use a steel ruler to measure this distance (Figure 3 and 4)

Figure 3

Figure 4

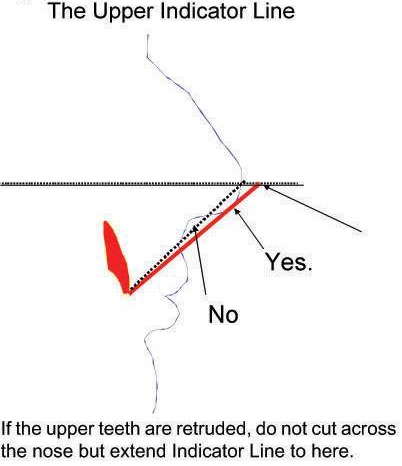

One caution is necessary when the maxilla is very retruded; the ruler must not be pressed against the nose but placed at a tangent to it and the line from the Tragus extended to where both lines meet (Figure 5)

Figure 5

If desired the line can be measured on a lateral skull x-ray but do not forget to allow for enlargement. Clearly this measurement is no more than an ‘indication’, nevertheless it is surprisingly accurate.

This unlikely measurement is now used to assess maxillary position throughout the world and is especially helpful for epidemiological studies where X-rays may not be possible. It provides an approximate guide of the relationship of the mid-face and the frontal bone, representing the ‘fullness’ of the facial profile. I have used the Indicator Line for over twenty five years and have found it invaluable. Not only does it provide an immediate assessment of maxillary position but it guides me during treatment, especially when deciding how far to advance the incisors or the maxilla and when to accept a compromise.

Peter Bushgang and his colleagues (1993) superimposed X-rays on SN and noticed that the “The upper dorsum (the area of the nasal bone) rotates upward and forward approximately 10 degrees between 6 and 14.” while “The lower dorsum (the area of the cartilage) rotates downward and backward in persons who show greater vertical and less horizontal growth changes”. These are relative changes but the most logical explanation must be because the saddle angle opens up increasing the angle between frontal bone and SN. Both Robinson and Bushgang presumed the nose was growing forward whereas I think the maxilla was rotating back. These changes can easily be measured by the increase in the Indicator Line.

It does appear that orthodontic retraction of anterior teeth emphasizes and perhaps increases the size of the nose, especially if accompanied by extractions. This pattern of treatment was common between 1940 and 1960 when many faces were badly damaged including my own. Sadly there are still many operators who extract and retract.

If the central incisors are not fully erupted, an assessment can be made using the occlusal plane. For a five year old it should ideally be about 28 and increase at approximately 1mm per year until puberty. In general girls are about 2mm less than boys. A simple rule is to add 23 to the age for a boy or 21 to the age for a girl. For instance if a boy is nine years old add twenty three and you know that his Indicator Line should be around thirty two millimetres.

It must be emphasized that these are ideals and are very rarely observed in industrialized societies as even good looking faces are likely to be increased by several millimetres. Some idea of ‘ideal’ values can be gained from various authors. Platou and Zachrisson (1983) studied a population of 568 twelve year old Scandinavian children but were able to find only 15 boys and 15 girls with class I occlusions and less than 1mm spacing or rotation. Reworking their material, I found that these boys had a mean indicator measurement of 43.9 (SD 2.79) while the girls were 41.5 (SD 2.62). The paper reported that the 30 selected children with ideal occlusion were “brachyfacial with somewhat procumbent incisors” compared with cephalometric norms and noted that “Remarkably the lower incisors were not behind the APO plane in any single case with ideal occlusion” suggesting that the mandible was also further forward. However the Indicator Lines of these boys and girls with ‘ideal occlusion’ were still nearly 4 millimetres higher that that suggested by the suggested ‘ideals’ and I am sure that this is a measure of the distance that the maxilla has to fall back before a malocclusion even starts to develop. Certainly my research with those living in more primitive environments has shown higher ratios of individuals with near ‘ideal’ Indicator Lines.

My belief is that it was the advent of cooking, circa 70,000 years ago, that led to the slow but progressive degeneration of the human occlusion and that any modern child who was brought up on a diet of unrefined, uncooked food, would develop normal occlusion. Living outdoors might also reduce the risk of allergies.

An unpublished study of my own, on 72 randomly selected twelve year old British schoolchildren (17 boys and 54 girls), showed that the Indicator Lines averaged 43.8 millimetres for the boys and 41.5 for the girls; remarkably similar figures to Platou and Zachrisson’s group. It is surprising that the British group, a number of whom had malocclusions, did not score higher. Kerr and Ford’s work (1986) would suggest that Scandinavians Indicator Lines are probably about 2 millimetres larger than Britons which may explain this but a number of children in the Scandinavian group had problems such as Bimaillary protrusion or lip apart postures which nay have introduced confounding factors.

Japanese ideals are about 2 millimetres less than British. Clearly the contrasts created by tall Scandinavians would also apply to small individuals from other populations. All this emphasises how difficult it is to find ideal faces and occlusions in industrialised populations.

I recently researched faces of the Masai tribe in Kenya. The average indicator line was just over 40mm, but several of them had Indicator Lines in the region of 37 millimetres. Deeper analysis of Platou and Zachrisson’s material shows that some conditions such as open mouth postures, and Bi-maxillary Protrusions are clearly related to maxillary position which can be identified using the Indicator Line. All orthodontists have experienced the irritation of children leaving their teeth and lips apart when the lateral skull X-ray is taken and I find it unsurprising that these particular children will have higher indicator lines. In Platou and Zachrisson’s case the Indicator Line was on average 2mm higher for the 10 boys and 8 girls who had their lips apart when the X-rays were taken, remembering that despite this all of them had ‘ideal’ occlusion.

Five girls were separately classified by these authors as having Bi-maxillary Protrusion, because their lips were “forward by more than 2 standard deviations”. Despite this

their Indicator Line was on average almost 2mm higher showing that despite the teeth being substantially too far “forward”, the maxilla was back and in fact their increased Indicator Lines suggests that this well known condition ought to be labelled “Bi-dental Protrusion” with the maxilla displaced down and back. In the same way nearly all patients with Anterior Open Bites have higher Indicator Lines (Figure 6)

Figure 6

These explanations may seem confusing until it is realised that in all these situations (as well as in class II division 1 and 2) the teeth may be displaced in one direction while the maxilla can be displaced in another, a very important concept to understand.

Logically the Indicator Line should stop increasing when growth ceases, however the work of Rolf Behrents (1985) suggests that facial changes (mostly lengthening) continues throughout life. While this may be true, the situation is complicated by difficulties in achieving accurate superimpositions over long periods. Behrents was using the base of the skull as his reference plane which can be affected by long-term changes in the saddle angle. My own research suggests that the majority of this change is due to vertical remodelling of the facial bones, rather than growth. There is a strong tendency for increased vertical changes in old age as the muscle tone degenerates allowing the maxilla to drop back; which is why old people’s noses so often appear to grow. This is associated with a flattening of the saddle angle as they get older.